How We Think: Logic, Patterns, and the Hidden Role of Association

Associative Thinking: More than Daydreams

The American Psychological Association (APA) defines associative thinking as “[A] relatively uncontrolled cognitive activity in which the mind wanders without specific direction among elements, based on their connections (associations) with one another, as occurs during reverie, daydreaming, and free association.”

While this definition captures a certain aspect of mental drift, it falls short of encompassing associative thinking's deeper mechanisms—particularly its role beyond conscious wandering. In reality, associative thoughts travel along specific neural pathways, feeding into executive brain areas where the Almost Gate continues its crucial function. Far from being confined to passive mental meandering, associations shape both our perceptions and reasoning, influencing how we assess incomplete information and navigate unseen elements in the world around us.

Our reliance on language often leads us to undervalue associative thinking, dismissing it as illogical or error-prone. True, it lacks the rigid structure of deductive reasoning. Yet, associative thinking is essential at every level, from processing sensory data to constructing abstract thought. The Almost Gate, a fundamental neural mechanism, selectively filters details—enhancing abstraction within a pattern while simultaneously introducing granularity to accommodate associated inputs.

This filtering is pivotal because, ultimately, each of us sees the world through a keyhole. The phrase “born with a silver spoon in his mouth” illustrates how experiences shape belief systems—formed not at birth, but through lived experiences and the gradual accumulation of knowledge, structured by associative processes that selectively reduce details while reinforcing familiar patterns.

And crucially, when facts are missing, we substitute associations as stand-in truths, shaping logical conclusions in ways that feel rational yet remain deeply dependent on past experiences. Perhaps this is the essence of Protagoras’s notion that “Man is the measure of all things”: our understanding is dictated not solely by facts, but by the associative frameworks through which we interpret them.

Associations Alone and With Logic

Patterns, similarities, and associations

Even when clouds obscure a mountain peak and dabs of oil paint scatter across the canvas in abstraction—as in Mont Sainte-Victoire—our minds instinctively fuse these fragments into a recognizable whole. Some may recall seeing such a view in person, others may have encountered similar paintings, and even those unfamiliar with the source still piece together the landscape from the selective elements Cézanne chose, completing the image in their own perception.

This recognition highlights a fundamental aspect of associative thinking: instead of analyzing isolated fragments, our brains form patterns by linking perceptual cues across varied contexts. Through Almost Gates, abstractions travel along neural pathways reinforced by experience, progressively shaping meaning until context-driven imagination completes the pattern—merging partial features into cohesive wholes.

Similarity arises when shared features connect items within a pattern, yet individual elements may retain unique details beyond the pattern’s core structure. This dynamic fuels abstraction, where associations form by substituting similar elements. These associations extend into logic, serving as flexible premises that shape conclusions—guided by details operating at varying levels of abstraction.

Reasoning by Analogy

When direct information is missing—or when a person seeks to evade inconvenient facts—analogies provide an appealing cognitive shortcut. By drawing connections between familiar concepts, analogical reasoning enables logical conclusions even when precise data is absent.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy gives this concrete example. “In 1769, Priestley suggested that the absence of electrical influence inside a hollow charged spherical shell was evidence that charges attract and repel with an inverse square force. He supported his hypothesis by appealing to the analogous situation of zero gravitational force inside a hollow shell of uniform density.”

For a more earthy example, consider Henry Kissinger’s strategic phrasing in the context of Nixon’s Vietnam War policies: “Withdrawal of U.S. troops will become like salted peanuts to the American public; the more U.S. troops come home, the more will be demanded.” The analogy leverages a sensory association—salted peanuts triggering cravings—to construct a persuasive narrative about escalating public expectations.

Reasoning by analogy is more than a convenience—it’s a powerful associative tool that guides decision-making when facts are unclear or unavailable. Yet, like all associative processes, it carries the risk of misleading connections that lead to flawed conclusions. Careful scrutiny is essential to ensure its proper application.

Imaginative Completion

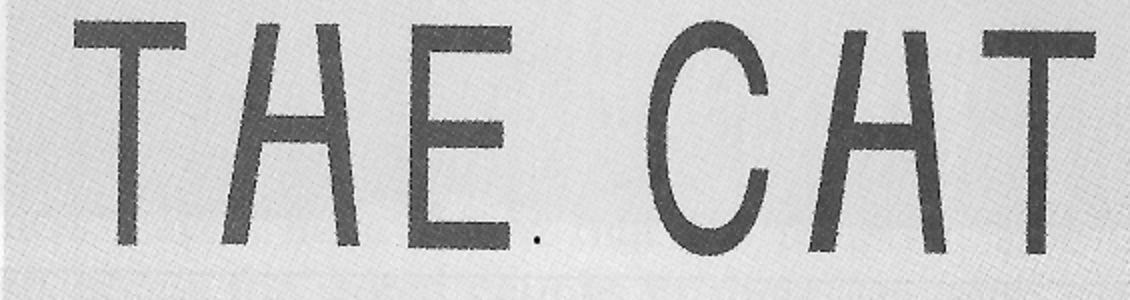

This figure provides a fascinating illustration of associative perception overriding raw sensory input. The phrase "THE CAT" contains letters that visually appear identical—specifically, the "H" and "A" share the same shape.

Despite this, we do not misread the phrase as "TAE CAT." Why? Context dictates interpretation. When the ambiguous shape appears between “T” and “E,” our brain instinctively selects "H" as the most probable fit. When the same shape is positioned between “C” and “T,” our experience with common words like “CAT” leads us to recognize it as an “A.”

This phenomenon illustrates that recognition is not purely exact matches—it is an associative process. The Almost Gates play an active role in shaping interpretation, favoring familiar patterns over a strict, pixel-perfect rendering of sensory data.

More broadly, this imaginative completion affects countless aspects of perception and reasoning. We do not merely observe the world—we construct meaning by integrating past experience, filtering sensory input in ways that align with established patterns. The brain’s associative mode is always refining our conclusions, ensuring coherence where logic alone might falter.

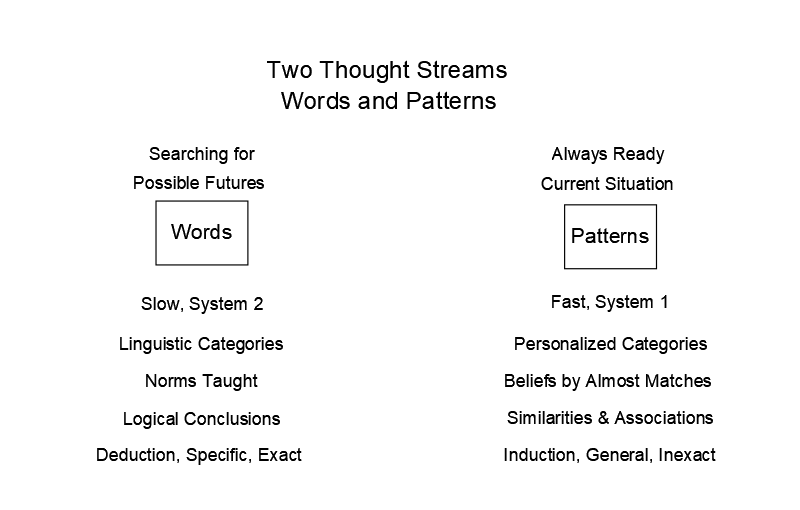

Thought Streams: Logic and Associative

Your mind operates through two distinct yet periodically connected thought streams—logic, which evaluates and refines conclusions, and association, which rapidly connects patterns and meanings. Rather than merging into a single thought process, they remain independent, each serving its own purpose: logic seeks the best response, while association is primed for immediate reaction. They occasionally exchange, interpret, assess, and sometimes accept the other’s perspective. Preconsciously, each forms internal representations of external situations, shaping initial responses. Once this information reaches the executive areas where consciousness resides, the streams engage in working memory exchanges. You may have noticed this when struggling with a decision—trying out different angles to see if they lead to a satisfactory choice. Often, these are associations being tested as potential logical premises.

Logical Mode: Structured, Deliberate, Precise

On the left side of the diagram, the logical mode aligns with the brain’s left hemisphere, which primarily handles words, structured reasoning, and precise categorization. This mode persistently evaluates how best to achieve our goals while mitigating risks and uncertainties. Yet, its methodical nature comes at a cost—logical thought is slow and deliberate, requiring intense cognitive effort to sift through countless possibilities before arriving at a well-reasoned conclusion.

Each thought in the logical mode is organized through language, social norms, and structured analysis—ensuring conclusions are correct, provided factual data is used. Keith E. Stanovich, in What Intelligence Tests Miss: The Psychology of Rational Thought, describes this mode as System 2 thinking, requiring a deliberate, step-by-step approach. To consider a future event, the logical mode replicates the current situation, introduces hypothetical scenarios, and evaluates their consequences. This iterative process can be exhaustive, often yielding insights but sometimes generating unnecessary complexity.

Logical reasoning is precise and deductive—specific, exact, and systematic—but it is not always the most efficient or adaptive approach. This is where its counterpart, the associative mode, takes the lead.

Associative Mode: Fast, Adaptive, Pattern-Based

The associative mode, depicted on the right side of the diagram, excels in recognizing patterns and generating rapid responses. Unlike its logical counterpart, it does not deliberate—it flows instantly, engaging deeply personalized neural lanes to interpret situations effortlessly.

Daniel Kahneman, in Thinking, Fast and Slow, describes this mode as System 1 thinking—fast, intuitive, and automatic. While he details its features, the neural Almost Gate provides the mechanism that makes them possible. This process leverages almost matches, identifying similarities between past experiences and current inputs. Through associative induction, it forms generalized patterns that may lack exact precision but prove remarkably effective in navigating uncertainty.

The Almost Gate governs abstraction levels within associative thought. Consider the following hierarchy:

Level 1: A broad category—"vehicle."

Level 2: A more specific classification—"car" or "truck."

Level 3: An even finer distinction—"sedan."

This layered abstraction allows the brain to selectively simplify or enrich sensory information depending on context, ensuring efficient pattern recognition.

Corpus Callosum: Bridging the Two Modes

The corpus callosum connects the two cortical hemispheres through 200 million neural fibers, integrating the activity of roughly 15 billion neurons. With a broad brush, we can say that every 75 neural steps, the hemispheres compare their respective interpretations—offering an opportunity for one side to replace its current neural summary with the other’s perspective. This constant exchange refines cognition, enabling each thought mode to select the most effective representation—whether a personal pattern or a familiar word—to best capture the situational nuance.

When Words Fail, Association Speaks

Ever struggled to explain why you feel a certain way, even when the sensation is clear? That’s your associative mode exerting itself, responding without a structured verbal framework. While logical thought demands explicit reasoning, associative thought captures subtle patterns and emotional cues, shaping instinctive responses that words alone cannot articulate. They can only hint at.

Understanding these two complementary modes enriches not only analytical reasoning but also intuitive decision-making—allowing you to harness the strengths of both structured logic and rapid association.

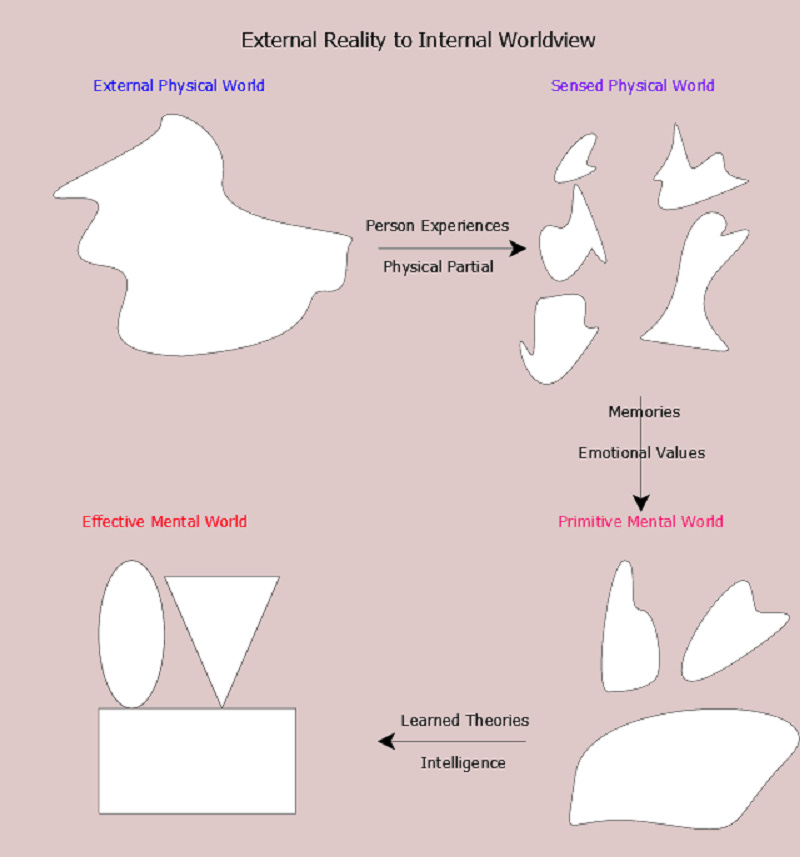

Understanding the Outside World

The associative mode is the dominant force in perception and situational assessment, shaping how we interpret reality. The diagram above hinges on the crucial role of the Almost Gate in filtering sensory input—structuring our understanding and refining our responses to the world.

At a broad level, sensory data undergoes three distinct stages before crystallizing into an adult’s internal worldview:

1. External Reality – The vast, complex world extends beyond our direct grasp, with only a fraction accessible through our senses—each constrained by specific limits. Sight is bound by visible wavelengths, touch requires direct contact, smell depends on airborne molecules, hearing is shaped by loudness, and taste is restricted to what reaches the mouth.

Filtered Perception – Our learned knowledge, past experiences, and emotional drivers refine incoming sensory data, often requiring surrounding context to fully recognize details that resonate with personal needs, fears, and goals.

Cognitive Integration – Through associations shaped by cultural context and accumulated knowledge, the brain imaginatively completes fragmented inputs, transforming them into actionable understanding for decision-making.

While associative thinking clearly draws on emotions to form similarities, logic is not immune to emotional influence either. Affective processes originate deeper in the brain than the cortex, shaping the motivations that determine which aspects of a situation we deem worthy of analysis.

Your Perspective

Do emotions form the foundation of consciousness, or do they compete with rational thought?

When making a difficult decision, do you lean on logic, recall past experiences, or trust your emotions? Or do you blend all three?

Share your perspective in the comments—let’s explore how cognition and emotion shape our choices!