Neurons: Engines of Signal Flow

Dendrites incoming, cell body summing, and when axon terminals deliver a signal

Neurons are the information‑processing units of the nervous system.

Before we get lost in the staggering complexity of the brain—with its 100 billion neurons and trillions of connections—let’s ground ourselves in the fundamentals. These basics apply to every neuron in the brain.

Physical Appearance

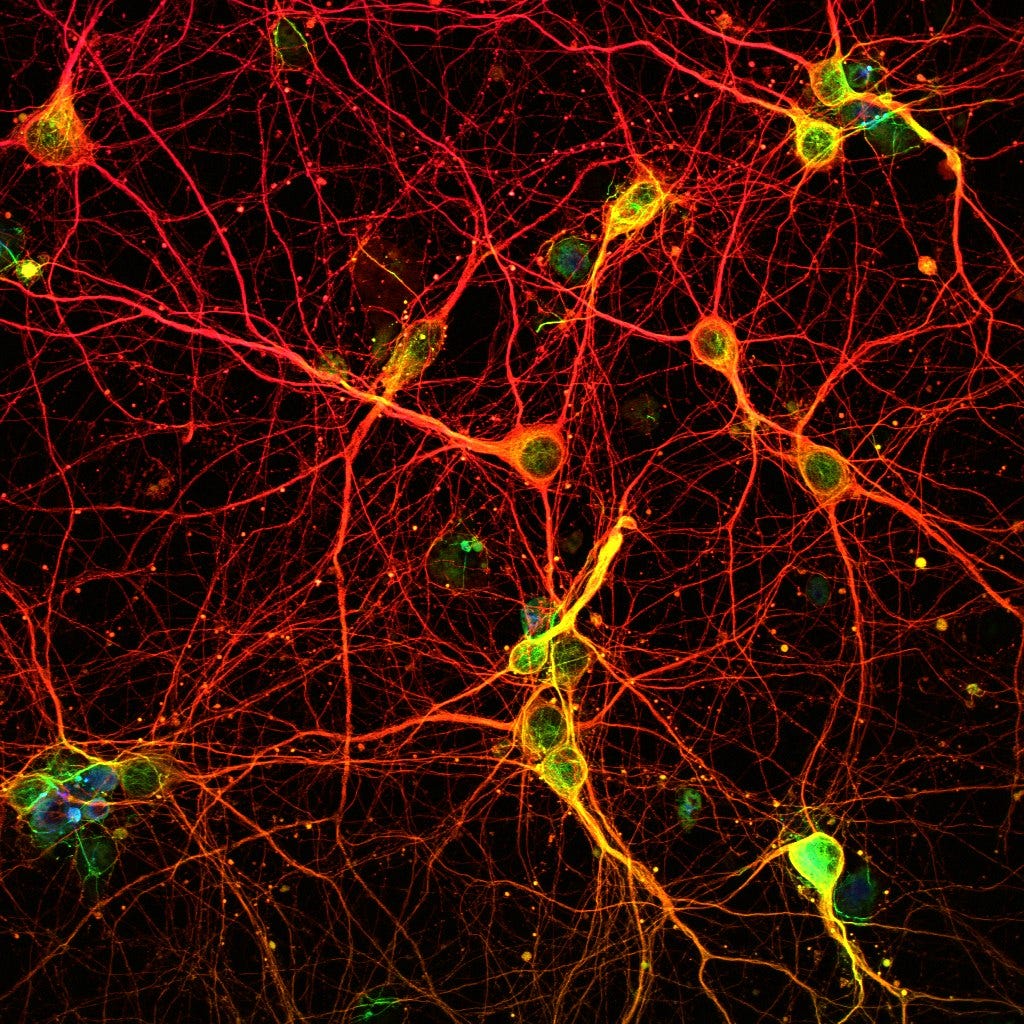

Figure 1: Neurons under a microscope.

The bright circular spots are the somas, or cell bodies. Even in this small slice, the density of connections is daunting.

Associative Mindworks focuses on brain neurons, not those in the spinal cord or peripheral nerves. To keep the discussion clear, I’ve set aside timing and frequency effects. These do not change the core principle: the threshold and the All‑or‑None rule. From the perspective of downstream neurons, all input sets that trigger a signal are identical.

So, let’s strip away the haze and focus on the essential parts of a single cortical neuron.

Neural Components

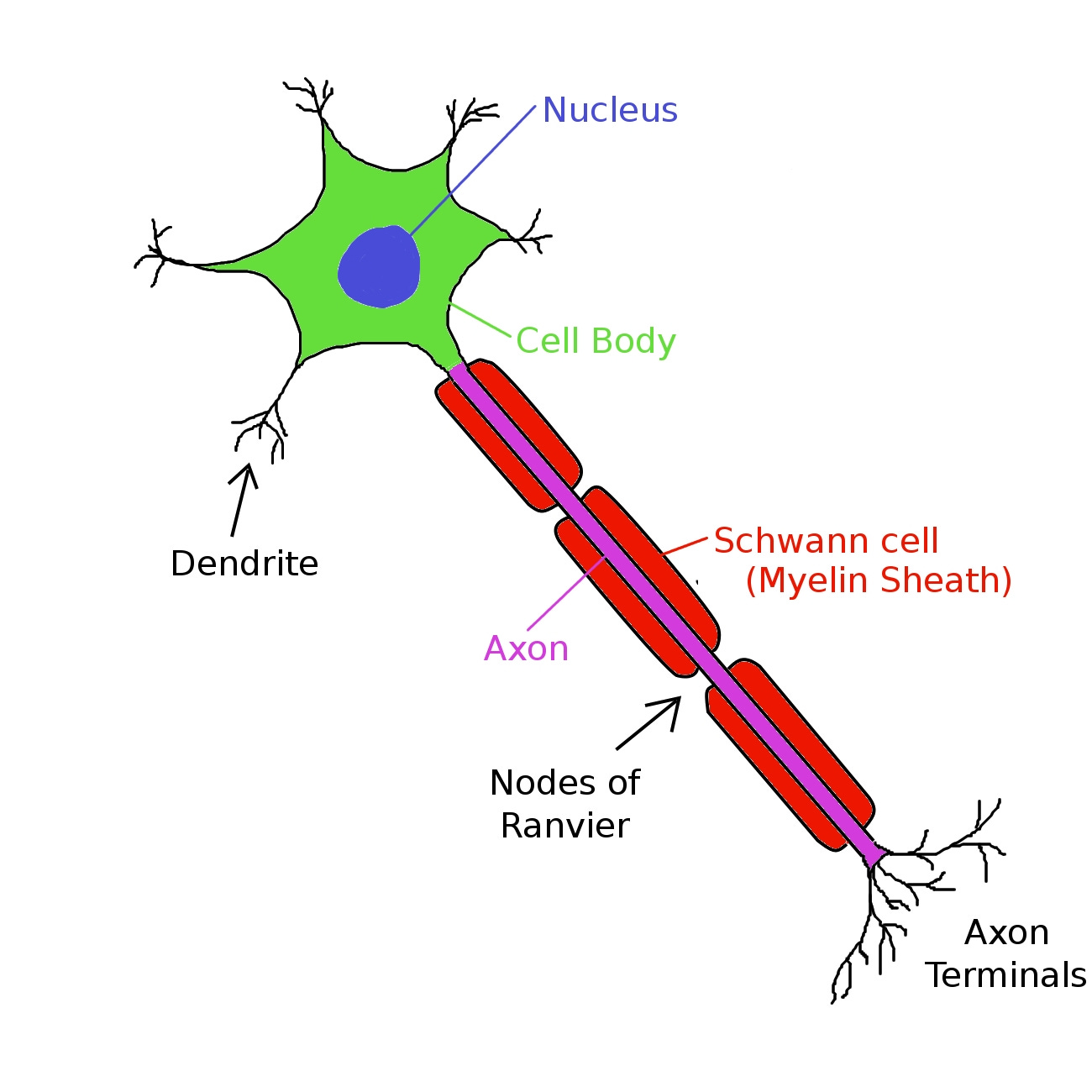

Figure 2: Labeled cortical neuron.

The nucleus sits inside the soma, or cell body.

Short branching extensions are dendrites, which receive inputs from other neurons or sensory cells.

The long extension is the axon, which carries the neuron’s output once triggered.

Sausage‑like segments along the axon, separated by nodes of Ranvier, regenerate the signal to ensure it remains identical all the way to its recipients.

Neural Threshold

Dendrites are the neuron’s input channels. They receive electrical signals from sensory cells and other neurons. A single cortical neuron may have up to ten thousand dendritic inputs. Of these, roughly seven thousand are excitatory, raising the neuron’s electrical potential, while about three thousand are inhibitory, lowering it. Excitatory inputs increase the chance of reaching the threshold for firing; inhibitory inputs reduce it. Importantly, these inputs are only active when their source neurons themselves fire—many potential connections remain silent at any given moment.

Inside the cell body, the nucleus integrates these incoming signals. The summed potential determines whether the neuron crosses its threshold. While this explanation focuses on summation alone, neuroscientists have shown that timing and frequency of inputs also influence firing.

When the threshold is exceeded, the axon carries a full electrical signal down its length. At the axon’s end, terminal knobs branch out to synapses, delivering the complete signal to many receiving neurons.

Synapse Connection and Gap

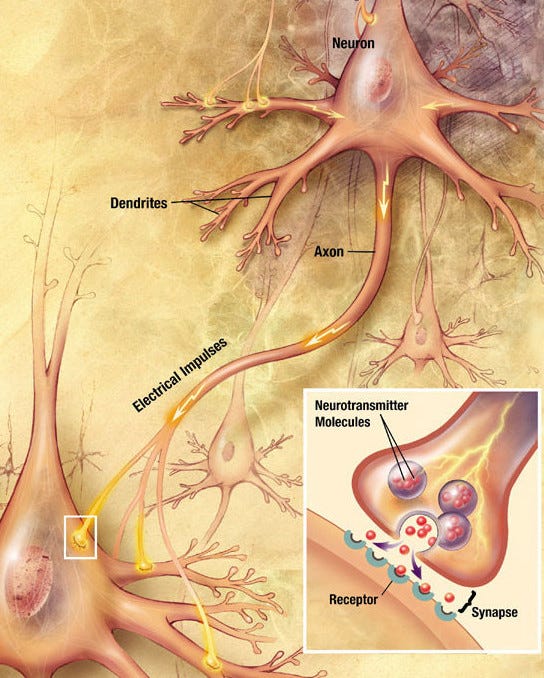

Figure 3. Synaptic gap.

The synaptic gap is the space where an axon terminal communicates chemically with another neuron’s dendrite. The electrical signal arrives at full strength, but the chemical transfer across the gap is adjustable. Its efficiency can increase or decrease depending on past activity. This weighting is explained by Hebb’s Law.

Nerves that Fired Together, Wire Together

When an axon of cell A is near enough to excite B and repeatedly or persistently takes part in firing it, some growth process or metabolic change takes place in one or both cells such that A’s efficiency, as one of the cells firing B, is increased.

Originally a postulate, Hebb’s idea has been confirmed experimentally, most notably by Eric Kandel (Nobel Prize, 2000).

This modification of synaptic transmission is the neurological manifestation of learning.

Looking Ahead

Deeper investigation into neural thresholds and the All-or-Nothing Principle sets the stage for the next concept: the Almost Gate Detailed Examination.

Sources

Figure 1. Neurons under a microscope. By ALol88 - CC BY 4.0

Figure 2. Neural schematic. By Nick Gorton - CC BY-SA 3.0

Figure 3. Synapse Chemical Schema. By Looie496; Illustrator Christy Krames, MA, CMI, for NIH – Public Domain

Kalat, James W. Biological Psychology, 8th Edition. Thomson Wadsworth, 2004. Print. ISBN 0-534-58836-6