Did Helen Keller think before she learned language at age seven?

Deaf and blind, she had no access to spoken or written words. Yet she developed home signs to communicate with her family. She expressed needs, desires, even frustrations. Was she thinking?

Of course—just not in words or images. Her thoughts were shaped by patterns of touch, smell, taste, and the rhythms of experience. This is the realm of Mentalese—the internal language of thought.

We’re taught to trust logic, to revere proof. But what about intuition, association, and analogy?

The Almost Gate newsletter argues that logic powers only half of our thinking. The rest? It’s messier, richer, and just as real. To understand this fuller picture, we need to look beneath language—at the symbols we use to think, and the rules that govern them.

Symbols

Words in Language

Most of us are familiar with internal dialogue—those strings of meaningful language fragments that echo in our minds, often guiding decisions and shaping our actions.

We learn to think this way through conversation: first at home, then in school, where verbal instruction trains us to reason, explain, and inquire using words. Language becomes the scaffolding for thought.

Patterns in Experience

But not all thinking is verbal.

Images, sensations, and sequences of experiences also form patterns that carry meaning. Even if you rarely think in pictures during the day, your dreams remind you that images can tell stories.

Just as words link to other words to form coherent thoughts, images lead to other images.

If you picture your child driving, and that image is followed by a memory of a news report about a car crash—that’s a thought, though a dreadful one.

This is thinking in patterns, not propositions.

Symbol Rules

Logic

Language brings with it built-in categories—hierarchies, relationships, and the ability to manipulate facts through formal rules.

When we think in words, we often think in logic.

Given enough facts, we can deduce consequences. We can weigh options. We can reason toward a decision.

Similarity

But pattern-based thought follows different rules.

Instead of using deduction, it moves by resemblance. Patterns link to other patterns through shared features.

These associations aren’t taught—they emerge from two sources:

· Our neural wiring, which sets thresholds for what counts as “similar enough”

· Our personal experiences, which shape what stands out, what sticks, and what connects

Neurons fire when there’s an “almost match,” and memory flows along paths of similarity.

A familiar smell might trigger a childhood scene. A shape might evoke a face.

And while shared features guide the flow, distinctive ones steer it in new directions.

When Patterns Lead, and Words Follow

Patterns and words operate in parallel, but they often collaborate in decision-making.

Patterns come first. Long before we speak, we learn that crying brings food, that warmth follows closeness. These early associations—formed through experience—shape our foundational worldview.

Because they’re built from personal experience, pattern-based associations are intensely individual. No two people share the same pattern map.

Words arrive later, typically in the second or third year of life.

Language offers a shared system of categories—ready-made labels for things, actions, and relationships. These verbal symbols are also patterns, but they’re socially constructed and culturally shaped.

As we acquire language, our internal dialogue begins to reflect not just our experiences, but our culture’s way of organizing reality.

Internal Worldview: The Lens of Decision

Our decisions don’t emerge from raw facts alone.

They’re filtered through an internal worldview—a mental model shaped by:

- Past experiences

- Emotional needs, goals, and fears

- Cultural categories and verbal reasoning

- Associative memories and intuitive impressions

This worldview is not a mirror of reality—it’s a personalized lens. And it’s different for everyone.

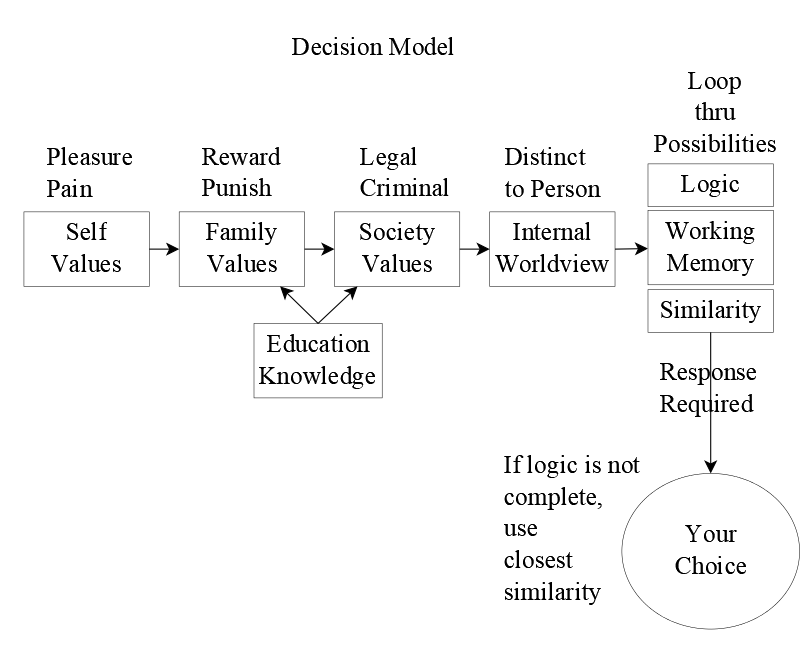

Decision-Making Schematic

1. Self-awareness begins with the pleasure–pain axis.

2. Family values are learned through reward and punishment.

3. Societal values emerge through exposure to norms, laws, and consequences.

4. Education and knowledge feed into both family and societal frameworks.

5. These layers combine to form your internal worldview—the stage on which decisions are made.

Two Modes, Two Timelines

- Fast decisions rely on pattern recognition. When time is short, the brain reaches for the closest match. It’s not always perfect, but it’s fast.

- Slow decisions allow for verbal reasoning. The logical mode can test different combinations of facts, compare outcomes, and even consult the associative mode for alternatives.

But logic has a weakness: it needs complete information.

When facts are missing, working memory can pull in associated patterns—hunches, memories, intuitions—and test them as if they were facts. Sometimes, this hybrid approach leads to a usable conclusion.

A Personal Example

A friend once debated which medical school to attend: a historically black institution or a general public one.

The decision wasn’t just about rankings or tuition. It was about identity, legacy, belonging, and future opportunity.

He struggled for months—not because he lacked intelligence, but because the decision touched layers of experience, he couldn’t fully articulate.

This is where logic falters and patterns make themselves heard.

Everyday Fog

Most of our decisions aren’t life-altering. But they’re still shaped by incomplete information, uncertain outcomes, and deeply personal beliefs formed early in life.

The logical path is often foggy.

Yet we must choose a path.

How Association Works in the Real World

I follow the financial media. One perennial question dominates: “Where are stock prices going?”

Everyone has an opinion—because no one has a theory that can reliably predict tomorrow’s opening price. Without such a theory, logical deduction can’t help you decide when to buy or sell.

Enter the Chartists.

They believe that past price patterns reveal future price movements. During the Great Recession of 2007–2009, they compared recent charts to those from 1929. They weren’t using logic—they were using pattern recognition, similarity, and association.

So what’s the takeaway?

Look at the results.

If the Chartists’ pattern-based decisions consistently yield gains, that tells them—and it tells us—that the pattern they’ve identified has predictive value. They haven’t deduced a theory; they’ve discovered a signal. And that signal may one day guide theorists toward a deeper understanding of stock price behavior—perhaps one grounded in sequential change. In this way, associative reasoning doesn’t just fill gaps in logic—it can lay the groundwork for it.

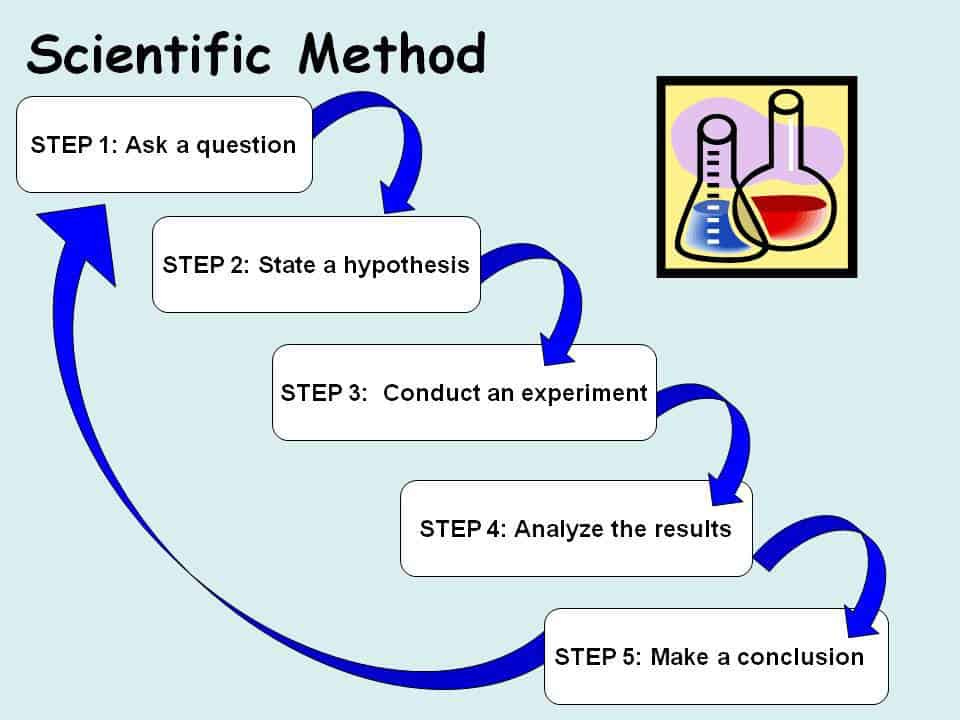

The Scientific Method: A Hybrid Model

Now consider science.

The hypothetico-deductive method (figure below) begins not with logic, but with a hunch—a hypothesis.

Often, that hypothesis arises not in words, but in abstract associations: a resemblance, a metaphor, a mental model.

Once proposed, the hypothesis becomes a premise.

From there, logic takes over:

- Deduce consequences

- Design experiments

- Test predictions

- Confirm or discard the hypothesis

The scientific method blends associative insight with logical rigor.

This same hybrid process underlies most of our thinking.

We form tentative hypotheses—often unconsciously—and then reason from them.

But unlike scientists, we rarely test our assumptions.

We rush to act, not to verify.

Mentalese & You

Despite those who dismiss intuition or unproven speculation, creativity doesn’t take sides.

It works with its sibling, logic—blending the fluidity of association with the structure of deduction.

Together, they give us the best of both modes: the spark of insight and the discipline to test it.

Words Make the World

I believe that learning language develops our verbal–logical stream of thought.

While I don’t subscribe to the strong Sapir–Whorf hypothesis—that language “defines” our internal worldview—I do agree with the weaker version: that the words we have affect how we think.

This plays out in working memory.

If a concept requires many words to describe, it consumes more working memory, more cognitive bandwidth—leaving less room for drawing conclusions or noticing associations.

In this way, crisp language empowers thought, while circumlocution constrains thought.

Recommendation: Let Your Mind Wander—Then Listen

Give yourself a break.

Set aside some undirected time—without your phone, games, internet, or music.

Step away from people and devices that steer your attention.

Let your deeper mind surface.

Notice the thoughts that rise unbidden.

They’re not distractions—they’re signals.

They reflect your concerns, your questions, your unresolved tensions.

They’re telling you what you need to hear to move forward, to feel more at home in your life.